Mitch Yawn was aware of something wrong before he reached the hives.

“I received a call. I was at work—working on an air conditioner. And she was—oh my God, she was just devastated,” he says.

“She” was Juanita Mae Stan-ley, Yawn’s then-fiancée The Flowertown Bee Farm is located in Dorchester, South Carolina. Stanley was also co-owner. Stanley and Yawn started the farm in January 2015 with the intention of selling bees to hobbyists as well as honeymakers. So far, they had 46 hives—a modest size, as bee farms go. Stanley and Yawn now own approximately 2.5 million bees.

Most of the dead were found on this hot August morning.

Firefighters were the first to notice dead bees. Many of the bees littered nearby the firehouse. They were not far away from Yawn’s apiary, which was located near a small lake. Stanley called Yawn, after seeing all the destruction.

Yawn recalls that “there were just dead bees everywhere.” They were picking them up in a large group.

According to court records, Clayton “Scott” Gaskins had directed a plane to apply deadly insecticides to certain areas of the county. Insecticides were ordered by the Department of Health and Environmental Control of the State (DHEC) to Gaskins. the Dorchester County Council ordered aerial spraying to kill mosquitos carrying Zika virus. It was done after Gaskins had reported that truck-based and ground-based crews couldn’t reach some of the DHEC target areas.

The bees were killed by the spray, and Yawn and Stanley’s new business was also destroyed.

This is a familiar pattern to many Americans. To prevent the spread of potentially fatal diseases, officials from government took drastic actions. These had devastating and direct consequences for small-business owners.

After the couple requested compensation for the loss, the court rejected the suit. Why? There is a long history of legal precedent for the “police power doctrine”.

Police powers have been used over the years to justify intrusive, state-based vaccinations. This power was also invoked by local governments to avoid having to reimburse homeowners whose homes were destroyed or inundated by Army Corps of Engineers SWAT teams. This doctrine allows states and localities to exercise great authority in the name public health.

Although it was happening at that moment, millions of bees were killed at Flowertown Bee Farm. This had no connection to COVID-19 which was many years off. These same police powers were used to justify lockdown orders during the pandemic. This included the closure of stores and restaurants for unspecified periods. These police powers were the cause of the deaths in Flowertown, their owners have not received any recompense and those whose livelihoods or businesses were affected by COVID-19 regulations are unlikely to get compensation via the legal system.

Yawn Stanley’s legal fight has been going on for many years and may soon end. It may have provided a path forward for property owners who were hurt by police power. The Flowertown case ruling is one reason to believe that courts will be more attentive when governments misuse private property rights for the sake of the “public good”.

The Smell Of Death

Yawn states that it’s difficult to believe this happened five years ago.

“One of my most cherished memories is about this…” [the bee farm]It would be so clean and fresh if one walked in that space. The atmosphere was different. He says it was alive and buzzing.” He said, “The bees just would be zipping about. The words are not mine. “All these bees were very busy working.”

He arrived at the scene exactly the opposite of what Stanley had hoped after his phone call. A few days later, when the two beekeepers went down to the apiary to do the real clean-up—after some scientists from Clemson University arrived to take samples of the dead bees and soil—it was even worse. “There was the smell death,” he remembered. “Rancid. Horrible.”

It is not uncommon for honeybees to die in massive numbers. Colony Collapse disorder (CCD) refers to a situation in which workers bees suddenly leave a hive and abandon it en masse leaving behind an helpless queen. This is something that beekeepers have been able to recognize even though scientists don’t know why.

However, the bee colonies that have collapsed look a lot like Roanoke Island’s mysterious disappearance. The colony vanishes without trace. The Environmental Protection Agency states that the most reliable indicator of CCD is the sudden loss in worker bee populations within a colony. There are very few bees near the colony.

The mysterious disappearance of the Flowertown Bee Farm was not what happened. It took place less than an hour away from Charleston. The Clemson review was inconclusive—despite the fact that investigators found “bees with behaviors consistent with pesticide exposure”—probably because samples weren’t taken soon enough. It didn’t take too long to find the culprit.

“Dorchester County knows that some beekeepers were affected by the spraying on Sunday,” Jason Ward, the County Administrator, told local media outlets. This was the same day Yawn Stanley and Stanley had found their hives destroyed. “I’m not happy that so many honeybees were destroyed.”

On Sunday 28 August, a plane zigzagged through Dorchester County in order to spray Naled. This common insecticide paralyzes the respiratory system of mosquitoes and kills them on contact. Though it can be dangerous to humans in high enough concentrations—and has been banned by the European Union since 2012—Naled breaks down quickly after being sprayed and is generally harmless to mammals and birds.

Naled, unfortunately for Stanley and Yawn and the 2.5 million bee-workers that they employ, is extremely toxic. These were not the only ones who suffered. Andrew Macke, an amateur beekeeper, told ABC affiliates that he couldn’t believe the notion of spraying poison from the air.

Aerial spraying was done to prevent the Zika virus from spreading in the air. This blood-borne illness can lead to serious birth defects and may be passed on to the child’s mother via an intrauterine transfer. An outbreak of the disease in Latin America during 2015–16 raised alarm about transmission by mosquitoes within the United States, though the vast majority of Americans who were infected caught the virus while traveling abroad.

South Carolina’s Department of Health and Environmental Control issued a warning to local governments about the possible Zika virus outbreak. Gaskins in Dorchester County was responsible. Court documents show that he sent two trucks out to kill Naled, but was worried about the mosquitoes in the areas where the trucks couldn’t reach.

Thursday, August 26th was a Friday for county officials to issue a press release in which they announced plans to aerially spray insecticides Sunday morning. In court documents, attorneys for Dorchester County argued that Gaskins maintained a list of registered beekeepers and that he had made calls to them—not as a matter of policy, but as a courtesy—to warn of the upcoming aerial spray.

Flowertown Bee Farm, despite being on the county list, was not called. The pilot who conducted the aerial spray on August 28, an Air Force veteran now working as a contractor for Allen Aviation, was provided with maps showing areas to be sprayed and areas to be avoided—including the location of known beehives in the county. According to investigators, he didn’t intend to spray Naled onto bee farms.

Federal Environmental Protection Agency has recommended spraying insecticides to limit Naled’s potential danger to honey bee colonies. Between dusk to dawn when the majority of bees remain in their hives. The sunrise in the last week of August is around 7:15 a.m. on the coast of South Carolina. The spraying of August 28th took place sometime between 6:30 and 8:30 am, according to court records.

Stanley and Yawn were killed by a combination of an overwhelming public panic, overly aggressive government responses, poor timing and some other unfortunate mistakes. They sought compensation for their loss, which they claimed was accidental.

Yawn reports that they had invested so much time and effort into the bees. “And it was over in an instant.”

Public Health Police Authority

These were the basic facts of this lawsuit. Stanley and Yawn lost millions of bees. County officials authorized aerial spraying deadly insecticide to be used on the dead bees.

The two beekeepers wanted compensation under the Fifth Amendment’s promise that the government cannot take property—or in this case, destroy it—without providing payment. The same principle would apply if Dorchester County officials took the bees to solve a honey shortage or to close Stanley and Yawn’s beekeeping business. The couple filed another lawsuit to seek compensation for damages under the South Carolina Constitution, which is very similar to that of the Fifth Amendment.

It is an established, fundamental principle in constitutional law. The claim was dismissed by the U.S. District Court.

“It’s undisputed that the spray was carried out to stop spread of disease,” Judge Margaret B. Seymour said in the summary ruling. “Such an action fits squarely within the state’s police power….Because [the county]it was exercising its police powers, not its power to eminent domain. The Takings Clause has not been implicated.”

According to Jeff Redfern, an attorney with the Institute for Justice, a Virginia-based libertarian law firm that was not involved in the Yawn lawsuit, this is a mistaken understanding of how the police power—which doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with cops—is supposed to work. This is a common mistake courts make.

Legally, the “police power”, is a shorthand for one portion of the 10th Amendment. It delegated powers not listed in the U.S. Constitution either to the states or the people. When the state’s regulatory and health power were much smaller than today in the 19th Century, the courts created the police power doctrine. This allowed municipalities to begin to regulate land use. To protect the public’s health, for example, it might be desirable that a municipality restrict certain types of industrial activity. This may constitute “taking”, in the most strict sense of the term, as land which cannot be used for certain purposes could lose value. However, courts held that this was not part of the established notion of eminent domain. Governments did not have to pay compensation.

As the power of the police grew, so did the authority granted to them by the states and the local authorities. It is deeply rooted in 10th Amendment. However, its current form didn’t emerge until early 20th-century, with the Supreme Court decision of 1905. Jacobson v. Massachusetts. This case saw the state law to allow municipalities to order smallpox vaccinations to residents to combat an epidemic in Boston. This ruling is still relevant today, as judges try to strike a balance between individual liberty and the state’s power in response to the COVID-19 epidemic.

One of these is the Jacobson A four-part legal test proved to be the right answer. The state’s power to authorize public health interventions would allow them if they were necessary, reasonable, proportional and did not cause harm. That power is what allowed mask mandates, business closures, as well other interventions during this current pandemic.

Redfern states, “In the 20th century, with the expansion of regulations, some private use property regulations could be considered takings” Redfern adds. The four-part Supreme Court test, which is vague and difficult to interpret, makes it hard to know what counts as excessive.

The courts have ruled that while governments must pay for compensation under eminent domain, they are often exempt from liability when they directly cause the destruction of property.

When a SWAT team destroyed a man’s home in the Denver suburbs while pursuing a suspected shoplifter in 2015—at one point cops drove a BearCat armored vehicle through an outer wall; the damage was so severe that the $580,000 home had to be torn down and rebuilt—the city offered to pay $5,000 toward the repair costs. John Lech (the homeowner) sued to get more damages. However, the city said that it was protected by its police powers. Federal courts also agreed and in 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Redfern represented Lech in this case’s appeals. He said that courts have a broad understanding of police power doctrine. “In practice, most local governments assume they are able to do anything they deem to be in public interest.” What Dorchester County was trying to do—indeed, what it succeeded in actually doing in the eyes of the U.S. district court—was to use the police power as a get-out-of-liability-free card.

This has implications for not only beekeepers in South Carolina, but also for all business owners who lost their profits due to the lockdown and shut down policies that were in effect during this current pandemic.

Federal Reserve data from April 2021 shows that around 200,000 American businesses were closed in the initial year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. This is more than any other year. Small businesses that rely on in-person interactions—barber shops, nail salons, and restaurants—were unsurprisingly the hardest hit. Although some businesses were forced to close due to changing consumer behaviour during the pandemic it is impossible to overlook the impact of government-mandated lockdowns. This was especially true in the first half 2020. Public health rules, such as bans on indoor dining and large-group gatherings, could also have negatively affected businesses, even those that remain open.

Are these business owners entitled to sue Yawn and Stanley for the damages caused by an aggressive government response to a public health risk? This is a difficult question that the courts will have to answer as the pandemic subsides, but it’s one they must consider.

Ilya Somin from George Mason University, who is a law professor, said that in an ideal world at least part of COVID shut downs’ burdens would be covered under the Constitution’s Takings Clause. Unfortunately, there is no precedent to support the exclusion of police powers from takings claims.

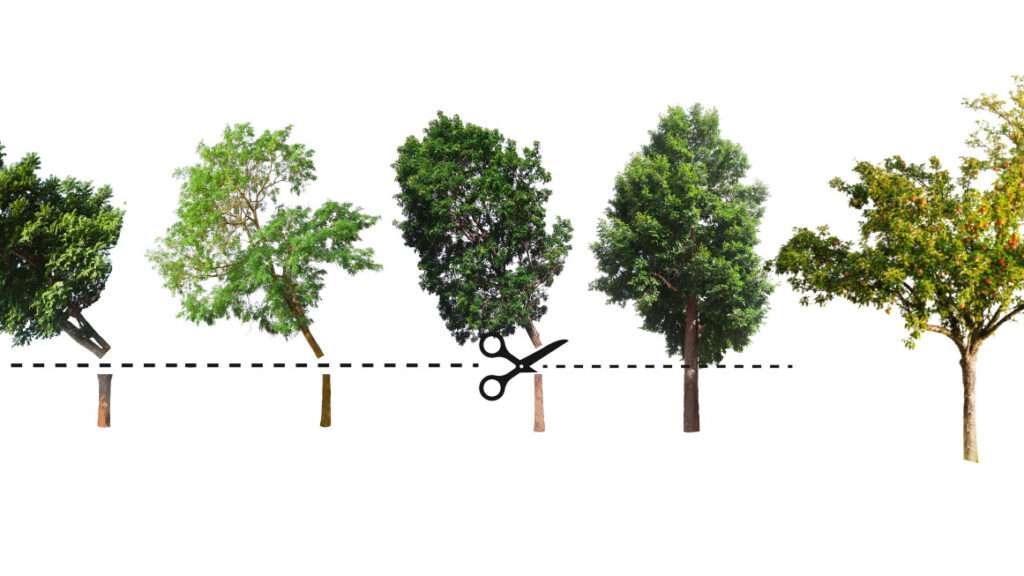

Somin specifically points out Miller v. Schoene, A 1928 case where the unanimous Supreme Court ruled that Virginia didn’t owe any compensation to an arborist who ordered trees to be removed to stop the spread of disease to nearby orchards. It’s a case that bears more than a passing resemblance to what happened in Dorchester County—and to what happened during the COVID pandemic. Each case involves state intervention to prevent the spread and destruction of property. 1978 is another important Supreme Court case that deals with the interplay of police power and the Takings Clause. Penn Central Transportation Company vs. New York City The court also ruled in subsequent cases that “temporary restrictions” on economic activity did not automatically make them takings.

Somin believes that current thinking about police takings and their interaction with them is “a mess.” This view must change to protect property owners rights. While there may be strong moral grounds for business owners being compensated for any harm caused by COVID-19 lockdowns in some cases, Somin believes it is unlikely that this will change anytime soon, other than incrementally.

There is a small chance of regaining the court’s confidence and there are some losses.

When Yawn and Stanley appealed their case, they may have nudged that incremental change along—even though they still lost.

J. David Breemer is an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, and was the lead counsel for beekeepers when they appeared before the U.S. Court of Appeals. It matters enormously because nearly everything that local or state governments do in regulating private property is a form of the police powers. So if the government is immune from the Takings Clause when it exercises its police powers, it can immunize itself from challenges just by saying ‘this was for public health’—and that’s never been the intent of the law.”

A three-judge panel from the 4th Circuit completed its review of Yawn’s and Stanley’s case in June. The lower court was upheld by the panel, which ruled that beekeepers are not entitled to compensation as their bees had been a “collateral damage” of the anti-Zika strategy in Dorchester County’s public health.

The ruling did however include an important twist.

Judge Stephanie Thacker stated that “government actions pursuant to police power aren’t per se exempted from the Takings Clause” In a Supreme Court 2002 ruling, John Paul Stevens (then-Justice) stated that the “torture to adopt” was a real danger. Each and every one rules in either direction must be resisted” in takings cases. This means that courts shouldn’t allow police to act as a liability shield for government governments.

Yet, Thacker still ruled in favor of Stanley and Yawn. She relied upon a collection of precedents from federal courts to establish that government do not need to compensate for any incidental harms caused by the exercising of police power. The fourth of four-part tests was created by the Jacobson ruling has to do with “knowingly causing harm.”) She wrote that the death of the appellants’ honeybees was clearly unintentional. While the death of Appellants bees is tragic, we can’t conclude it was the foreseeable result or probable outcome of County’s actions when there is clear evidence of collateral damage arising from County’s mosquito control efforts.

This distinction is important but not necessarily satisfying. This allows governments to avoid liability. accidents but gives judges discretion to determine whether the loss of private property was a deliberate or foreseeable result of a public health action. The document also discredits the idea that police power is unlimited.

Breemer states that the recognition that police power is not exempted from Takings Clause claims means property owners will be more likely to have their claims defended on the merits than being dismissed. Breemer states that even though property is destroyed, they still must answer to the Constitution. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you will have to pay if you cause property damage in the name of public health. may “

Because of American law’s nature, change is often slow. A single case will not end a decade of precedent that was based on faulty reasoning or false dichotomies. Reformers need to build new precedents. Even a single sentence in a losing decision can open up opportunities for another result in another courtroom.

You might have noticed it already. Redfern, Texas, is currently advocating. Other case in which SWAT officers destroyed a home while pursuing a suspect—this time by using explosives to blast a hole in the home, even after the homeowner handed over keys to the police when they arrived. The defendant cites in court documents the 4th Circuit ruling. Yawn v. Dorchester County as a reason the judge should not simply dismiss the compensation claim on police powers grounds. He says that any clarification in the way courts weigh takings claims against the police power would be beneficial for property rights because the current test, as it is applied, could not be better.

The city of McKinney in Texas tried to have the SWAT lawsuit dismissed. A federal judge, however, rejected the attempt. Judge Amos Mazzant stated that the plaintiff had “plausibly claimed the destruction of her house by the City as a result of the exercise of its Police power could amount to an taking”. It allows the case move on to the phase where it can consider the merits.

This is more difficult than you think. For governments to be forced to pay for the abuses of police power, it is necessary to convince courts that police powers are no longer considered a shield against liability.

While the effort will be continued in court, state legislators and governors may also get involved. The possibility of limiting the police’s powers, and the resulting erosion of property rights, is for laws to be passed that will require government to pay more compensation in certain circumstances. Redfern cites a Colorado effort that resulted in an amendment to Colorado’s state constitution. This was in 2018. Redfern points out that Amendment 74 required the government to pay just compensation for private property owners if a regulation or law of government reduces its fair market value.

The proposal in question was in response to an earlier Colorado law which banned drilling for oil and natural gas in vast swathes. This led to lower property values. This amendment may signal that courts should prioritise taking claims over any other claims, like those involving police.

Too bad that we will not be able find out what the Colorado amendment means for the law. Voters in the state rejected the proposition at the polls. It was opposed by many local government officials.

However, there are still many opportunities. COVID-19 represents perhaps the most significant test for local and state police power. Many places that people meet in large groups, such as churches, cinemas and movie theatres, were shut down or forced to operate at a reduced capacity. Although it might not seem as dramatic as a SWAT team destroying someone’s house or the death of millions bees in a disaster, the facts are very similar. These situations all involve governments trying to ensure public safety and health by imposition of huge fees on the private sector.

New Mexico’s and Pennsylvania’s supreme courts have both heard COVID-19 restriction cases. These were deemed violations of the Takings Clause. The courts dismissed both challenges on the ground that police may be used by governments to deal with a crisis in public health.

The recent SWAT case in Texas shows that the Texas ruling is not final. Yawn It did not open up the doors to judges who would compensate victims of COVID-19 lockdowns. It might have been able to open the door slightly.

“Yawn indicates that it is improper,” Breemer says, for courts to immediately dismiss takings claims just because the government invokes the police power. This means that courts have to consider all aspects of the closing situation and not just the government’s need to solve a medical crisis.

Love and Bees

Flowertown Bee Farm has been in decline for more than five decades.

Stanley and Yawn did not fully rebuild their business. In order to survive, the couple sell their beekeeping equipment to both professionals and amateurs. They never got back into the business of breeding bees and building out hives—it was too much work, knowing it could all be wiped out so quickly. The legal drama was a distraction, but the bee lovers found time to wed.

Dorchester County changed the way it notifies beekeepers about future aerial sprays after the controversy sparked by the accidental killing of Flowertown honey bees. What is the new policy? No notification at all. The beekeepers have been responsible for keeping an eye on county websites and notifying one another as needed since May 2019.

While Naled is still being used in South Carolina today, it has been controversial in some other locations. Protests against widespread insecticide use are raging Puerto Rico’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 by then-Gov. Alejandro Javier Garcia Padilla outlawed aerial sprays with Naled. There were protests also against the use of Naled in Miami when Zika was endemic. Both places were able to use the insecticide. Public health officials credited him with helping stop the spread of the virus.

Was there any concern about Zika? With the COVID-19 pandemic now in full swing, panic surrounding Zika seems more exaggerated. The CDC recorded 5,168 Zika cases in America in 2016. The vast majority of those—4,897 of them, to be precise—were identified in travelers returning from affected areas in other countries where the disease was more common. According to the CDC, only 224 of these cases were transmitted by mosquitoes. Not one of them was from South Carolina.

The absence of mosquito-borne disease outbreaks in Palmetto State is not a reason to stop spraying Naled from aircrafts on Dorchester County. The aggressive tactics taken by local governments might have kept the disease from spreading. Also, insecticides are used to kill mosquitoes. Other benefits can be realized for humans by the reduction of the transmission of deadly diseases carried on the insects.

Beyond the legal issues, which can be narrowly esoteric and complex, there are wider moral and ethical questions. Stanley and Yawn are not able to feel that justice was done. The federal appeal was denied. Lawyers involved in the case claim that the ruling of the 4th Circuit does not allow for an appeal to the Supreme Court.

The lawsuit against the couple in state court is continuing. Yawn said that he hopes for compensation from the government. However, he doesn’t anticipate it.

Although the police power was intended to allow governments to safeguard public health, the Supreme Court warned decades ago about the danger of a slippery slope. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote 1922 that “if instead the private uses of property were subjected to unbridled uncompensated qualification underneath the police power,” “the natural tendancy of human nature is to expand the qualification until finally private property disappears.”

Today, the police power seems to have become a tool for excusing governmental failure—or justifying governmental expansion. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor stated during the recent oral argument, even members of Supreme Court are guilty of this confusion. While questioning Ohio’s solicitor general over the merits of having the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration enforce the Biden administration’s vaccine mandate—a clear exercise of the police power—Sotomayor said she did not “understand the distinction why the states would have the power [to enforce the mandate]However, the federal government won’t.

This is also an axiomatic answer: The 10th Amendment grants the states all power not specifically granted by the federal government. Long-standing court cases have shown that the police are solely the responsibility of the state (and any entities created by them, like counties and municipalities).

The Yawn This case illustrates the problems that may arise when government officials embrace a broad view of police power. These failures were experienced at many levels in South Carolina. Aerial spraying was an inefficient response to a poorly defined public health risk. It was not done according to the procedures intended to minimize unintended effects. The legal system did not make the victims whole due to the decades of court precedents which never changed in the light of growing police power.

Police power gives broad authority to local and state officials. However, they are not required to answer for their actions when these powers are misused to hurt constituents. In circumstances where private citizens are held accountable, there is no reason courts should grant government officials mulligans.

Local and state officials often view public-health issues as blank checks to allow them to be reckless and destructive with little risk of legal backlash. It is important for them to recognize the need for laws that limit their impulses. A system that completely relies on the good judgement and discretion of those with unlimited authority will be doomed to failure.

Yawn text me soon after Yawn finished sharing his story. “After we left, Yawn sent me a text. [Stanley]. He wrote that she had tears in her eyes. It still breaks her heart, even after all these years.