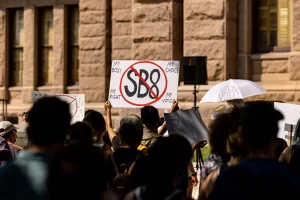

The Supreme Court released its decision today on Texas SB 8 – a controversial anti-abortion statute designed to bypass judicial review. In previous posts, I explained how Texas SB 8 was designed to evade judicial review. As I have explained in previous posts (e.g. here and here), this case centers on whether Texas has the ability to evade judicial oversight by delegating enforcement power exclusively to private litigants. SB 8 seemingly bars enforcement by state officials, and instead delegates it to private litigants, who each stand to gain $10,000 or more in damages every time they prevail in a lawsuit against anyone who violates the law’s provisions barring nearly all abortions that take place more than six weeks into a pregnancy. It would be a precedent that other constitutional rights are not subject to judicial review if Texas’s tactic succeeds.

Today’s Supreme Court decision in Whole Woman’s Health V. JacksonPreenforcement suits against SB 8 can be filed. However, only state officials on the medical licensing boards are allowed to proceed. Eight of nine justices concluded that they still had some enforcement authority under SB 8. The Attorney General of Texas, the state judges and state court clerks as well as the private litigant that was involved in the case are all denied relief. Justice Neil Gorsuch and three other conservative justices (Barrett Kavanaugh, Alito, and Alito), voted in a plurality that relief against AG is impermissible. They also ruled against relief against state judges and clerks because those interests do not conflict with the SB8-discontinuing providers.

S.B. suits may be brought by private parties. 8 suit in state court might be against petitioners. However, the state court clerks that docket these disputes are generally not the same as the state-court judge who usually decides them. Clerks file the cases when they are received, but do not participate in disputes. Judges are there to settle controversies regarding a law’s meaning and conformity to the Federal or State Constitutions. They do not have to fight the other side in litigation. This Court explains that “no case or controversy exists between a judge who decides on claims under a statute” and a litigant who challenges the constitution of the statute.” Pulliam v. Allen, 466 U. S. 522, 538, n. 18 (1984).

Justice Gorsuch believes that plaintiffs could bring a preenforcement case against officials in state medical licensure. This issue is agreed upon by eight out of nine justices, except Justice Thomas.

Some petitioners are barred from relief by this Court, but others remain. Thomas, Allison Benz and Cecile Young are the petitioners. Based on the argument and briefing, we see that the petitioners Thomas, Allison Benz, and Cecile Young fall under the historic exemption to state sovereign immunity Ex parte Young. These individuals are each executive licensing officials who can or must enforce the Texas Health and Safety Code including S. B. against petitioners. 8. See, e.g., Tex. Occ. Ann. §164.055(a); Brief for Petitioners 33–34. We hold therefore that petitioners can still sue these defendants for their sovereign immunity at the motion-to-dismiss stage.

Gorsuch continues to disapprove Justice Thomas’ single dissent, arguing that licensing officers are not appropriate defendants.

JUSTICE Thomas suggests that licensing-official infringers lack the authority to enforce S. B. 8. This is because the statute states that it will only be enforced by private civil actions.[n]However, . . Any other law.” See Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. §171.207(a). The same provision in S. B. The same S.B. 8 provision also says that law “mayn’t be construed as. . . Restriction on the enforceability any other laws that regulate, or ban abortion. §171.207(b)(3). The saving clause is important because the licencing-official defendants, according to the briefing, are abortion.

Consider, for example, Texas Occupational Code §164.055, titled “Prohibited Acts Regarding Abortion.” The Texas Medical Board is required to comply with this provision.

Take appropriate discipline action against any physician who has violated. . . Section 171, Health and Safety Code”, a Texas part of statutory law, which also includes S. B. 8. It appears that Texas law gives licensing-official defendants the duty of enforcing a law that “regulates”.[s]Oder interzice[s]S. B. exempts abortion from its duties 8’s saving clause…..JUSTICE THOMAS presents an alternative argument. He emphasizes that it is important to keep a

suit consistent with this Court’s…. precedents. It isn’t enough that petitioners “feel infected” or “chill.”[ed]’ ” by the abstract possibility of an enforcement action against them…. They should, instead, demonstrate at most a plausible threat of this enforcement action

against them…. [W]These observations are in principle acceptable. We disagree with their application to this particular case. They have alleged that S.B. 8 has already had a direct effect on their day-to-day operations….. And they have identified provisions of state law that appear to impose a duty on the licensing-official defendants to bring disciplinary actions against them if they violate S. B. 8. We find that this suffices at the motion-to-dismiss stage and suggests to petitioners they will be subject to an enforcement action. Therefore, we allow the suit to continue.

If the plaintiffs prevail in their lawsuit against the licensing officials, they will, most likely, be able to get an injunction that applies only against those defendants. The precedent can be used to protect against private SB 8 lawsuits and should therefore eliminate the “chilling effect”, if any, of SB 8.

This will allow the plaintiffs relief from SB 8 should it be deemed unconstitutional by federal courts. Justice Gorsuch points out that there are also state-court preenforcement litigation against SB 8. This resulted in yesterday’s decision against the enforcement mechanism. The SB 8 tactic is unlikely to protect SB 8 from preenforcement review. It remains to be seen if other states and Texas can insulate similar laws against judicial review.

Justice Sotomayor’s partial disobedience for the liberal justices suggests that the states may be able to do exactly that by simply going further than SB 8 in preventing enforcement by government officials

My dissatisfaction with the Court goes beyond a dispute over whether petitioners can sue as many defendants. This dispute centers on whether States have the right to nullify federal Constitution rights through schemes similar to this one. They can, provided they make their laws more clearly to disclaim any state enforcement, licensing officers included, the Court ruled. It will be a costly decision that Texas makes to withdraw from federal supremacy. I doubt the Court, let alone the country, is prepared for them…..

[B]The Court forecloses suit against the state court officials and state attorney general. This allows the States to re-create and improve Texas’ plan to use the future to seek the exercise of every right that this Court recognizes.

It is not a hypothetical. S. B. has many possibilities. Eight more are planned. Since the Court’s failure to stop the law being implemented, several States legislators have introduced or discussed legislation to replicate its plan to displace local rights. How can federal courts handle a situation where a state prohibits worship of a religious minority through heavy “private” legal burdens, which are amplified with skewed court processes, but is doing a better job than Texas by disclaiming any enforcement by state officials. The Court says that perhaps nothing. Even though there may be a path for relief that is not yet recognized, this Court has now blocked the easiest route according to its precedents. It is a mistake that I am afraid the Court and the country will regret.

It is an actual danger. It is one of the reasons I support SB 8 plaintiffs as well as many others who are concerned about other constitutional rights being threatened. However, because of the power of modern regulation, litigants may often, if not always, be able find some local or state regulatory official who is somehow connected to the enforcement of the law. Justice Sotomayor suggests that the “religious minority” could be subjected to regulation by the state officials responsible for enforcing laws involving non-profit organizations, officials responsible for regulating land use, and other officials who are charged with overseeing the use of property by the officials.

Other indirect connections could be sufficient to permit the case to proceed, even if the weak connection between SB 8 and the medical licensing boards is enough. Justice Gorsuch also points out that the “”[t]He petitioners have pled that S. B. 8. has already had an effect on their day to-to operations” is one of the reasons their case against the licensing officers can proceed. The “direct effect,” is, of course, brought on by plausible fear of ruinous litigation. This might be a factor in some other cases.

The bottom line is that it could be hard for states to protect SB 8-like statutes from judicial scrutiny. It might be impossible to prevent all possible indirect enforcement powers of various state or local officials. There are many tax exemptions available for private entities and individuals, as well as land-use regulations and licensing rules. All of this could have at most a slight connection with an SB 8-style bill.

However, it is not clear what the future impact of SB 8-like legislations will be. As state governments attempt to shield these kinds of schemes from judicial scrutiny, private parties that are being targeted by them seek to sue state or local officials based on some connection with the law. We can expect to see a cat-and mouse game. The federal courts will have to deal with the cases individually.

This makes it more difficult for future cases to be resolved. Justice Gorsuch has four votes in support of his opinion. Justice Thomas’s opinion, which would have prohibited all anti-SB 8 litigations, gets only four votes. Chief Justice Roberts’ decision to allow suits against Texas attorneys general and state court clerks receives four votes. Justice Sotomayor, who would be more than Roberts in certain ways, has only the support of three of the Court’s liberals.

Gorsuch’s opinion will likely be interpreted by the lower courts as being binding. United States v. Marks(1977), which means they must credit the Supreme Court’s opinion that resolved the case on “narrowest grounds.” However, the question is not one that can be easily resolved. A further problem is that it’s not obvious how tightly the connections between the state regulators of law enforcement are needed to permit a lawsuit against one another.

These problems could all have been avoided had the Court adopted the sensible position advocated by Chief Justice Roberts, in his partial concurring view.

Several other respondents, in my opinion, are proper defendants as well. First, Texas law gives the Attorney General coextensive authority with the Texas Medical Board in order to investigate violations of S. B. 8. If a doctor violates any rule or order made by the Board, the Attorney General can “instigate an action for civil penalties.” Tex. Occ. Ann. §165.101….

Penny Clarkston (a court clerk) is the same. The State laws are not always enforced by court clerks. Ante, at 5. However, by design the mere threat that even unsuccessful suits are brought under S. B. 8. This is a chilling act that’s Constitutionally protected, considering the rules the State has set. These circumstances make it impossible for court clerks to issue citations, or docket S. B. The scheme to enforce S. B. is unavoidably included 8 cases. 8 cases are unconstitutional and therefore must be included in the scheme to enforce S. B.[ed]”to such enforcement as to be proper defendants. Young, 209 U. S., at 157. S.B. Clerks’ role in the matter 8. This is different than the role played by judges. In no way are judges adverse to parties who have to bear the S. B. burdens. 8. But as a practical matter clerks are—to the extent they “set[ ]In motion the machinery” which places these burdens on people sued under S. B. 8. Sniadach V. Family Finance Corp. Bay View, 395 U. S. 337, 338 (1969).

Justice Gorsuch did highlight some other options for judicial review in the case. These include preenforcement actions at state courts of the type already being taken against SB 8. However, state law could prevent actions in state courts. Federal courts also have the primary function of providing a venue for constitution claims against the state and local government that is not subject to the authority of any of them.

The ultimate consequences of the SB case are still unknown. They will be litigated in the future. The only ones who are truly happy with the result today are the attorneys who get more business as a result.