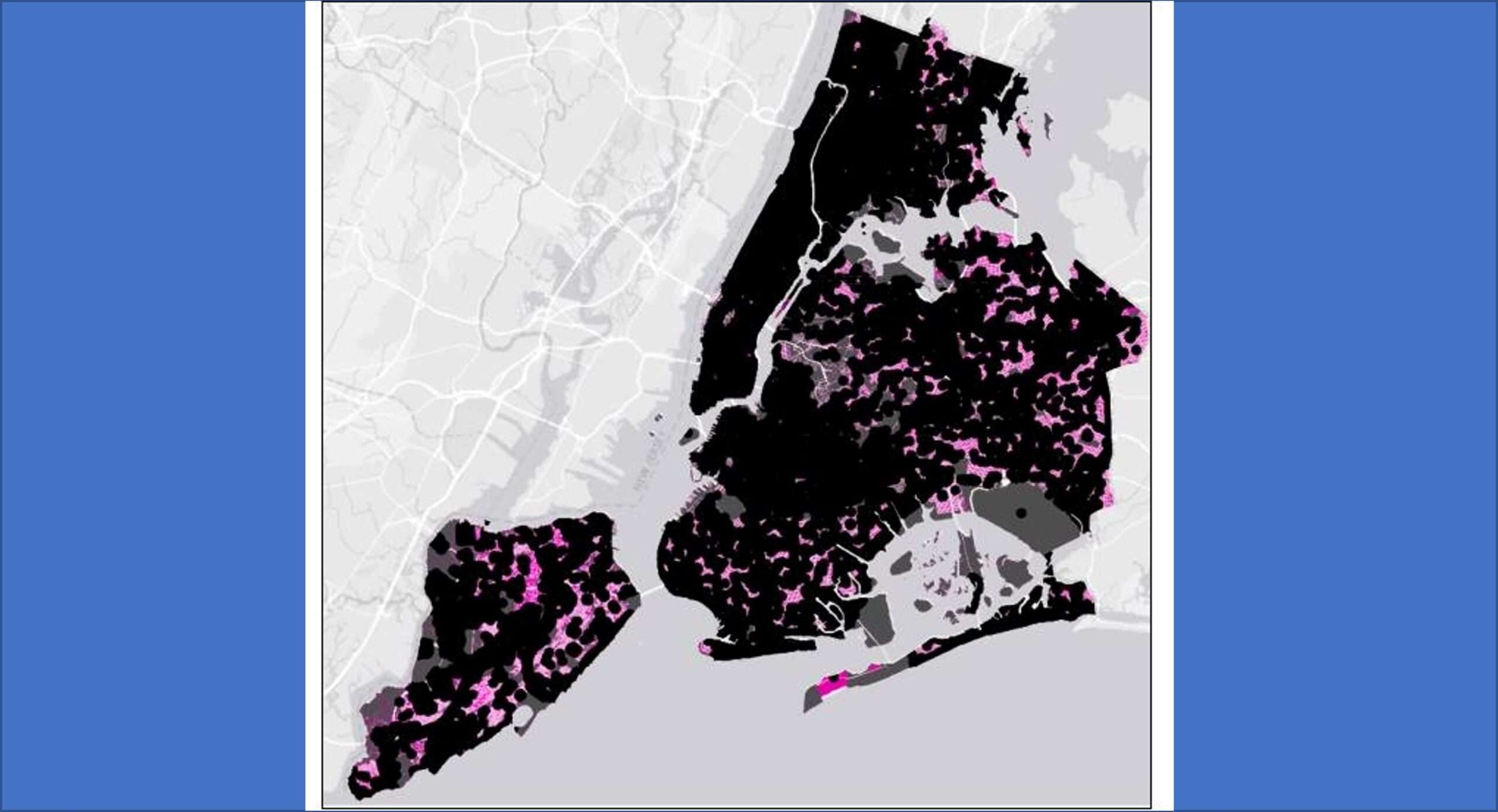

New York’s 2005 sex offender registry has banned people living within 1,000ft of schools from being on “level 3”. These “buffer areas” are found in nearly every residential area of New York City. These restrictions are enforced by the state and require that registrants find legal compliant housing prior to leaving prison. This means they could remain in jail long after their conditional release is granted or even after serving their initial sentences.

Angel Ortiz suffered the same fate. In 2008, he was accused of being “sexually active”.

A robbery involving pizza delivery men was carried out by a threat to a pizza deliveryman.

Secure money to purchase drugs. Ortiz was sentenced after pleading guilty to attempted sexual abuse and robbery. He also received 10 years imprisonment plus five years parole. After serving eighteen and half years, he was eligible for supervised freedom. He was eligible for supervision release, however. New York Times reporter Adam Liptak notes, Ortiz remained in prison because all of the housing options he suggested—his mother’s apartment in New York City, along with “dozens of alternatives, including some in upstate New York”—ran afoul of the 1,000-foot rule.

Ortiz remained behind bars even though he was freed from the original 10 years sentence. Because of New York’s restrictions on residence, Ortiz was able to serve an additional 25-months.

The Supreme Court refused to hear a New York Court of Appeals ruling that had upheld Ortiz’s continued imprisonment. Justice Sonia Sotomayor acknowledged that the case did not meet the criteria of the Court for granting certiorari, but she also highlighted the “serious constitutional issues” raised by New York’s residence restrictions. She suggested they “may not be able to withstand even rational basis review.”

Because that review standard is very deferential, and only requires a “rational relationship” between a restriction of liberty and a legitimate state interest, Sotomayor’s assessment makes a clear statement about the weak justifications for New York’s residence restrictions. It is in line with the findings of criminologists who found little evidence to support the policy’s safety. Numerous courts and agencies agree that restrictions on residence do not work the way they are advertised. They may be counterproductive and undermine rehabilitation, increasing the likelihood of recidivism.

Sotomayor referenced a report from the Justice Department in 2017 that stated there was “no empirical evidence” for residence restrictions being effective. The Justice Department stated that there is “no empirical support for the effectiveness of residence restrictions.” It also noted that it may have “a variety of unintended negative consequences” which “aggravate rather than reduce offender risk.”

This assessment is supported by a study that examined 3,166 sexual offenders released from Minnesota prisons in the 1990s and 2002. Grant Duwe, a criminologist from Minnesota, reported that the 2006 report was in Geography & Public SafetyThe “reincarcerated for another sex offense” had resulted in 224 of the offenders being released. Duwe and his associates examined the new crimes to see if they were affected by restrictions on residency. The team asked Duwe and his colleagues if the crime involved direct contact with victims younger than 18, within one mile of the residence, as well as whether that contact took place “near any school, park or day care center” or another restricted area.

Duwe, the Minnesota Department of Corrections’ research director, discovered that no of the 224 sex crimes would have been stopped by a residence restriction law. Residence restrictions are aimed at children’s areas, but the 79 offenders that had direct contact with victims were more likely to be juveniles than they were for adults. Duwe noted, “sexual recidivism is affected by residential proximity, and not social or relationship proximity,” that “sex offenders seldom established direct contact to victims close to their homes.”

Duwe stated that these results, along with other research, suggest that residence restrictions will have, at most, a minimal effect on sexual recidivism. However, he warned against the possibility that such policies might be harmful or even fatal. Duwe stated that recent research shows that the lack of permanent, stable housing can increase the chances that sex offenders will abscond and reoffend. Residentiality restrictions could make it more difficult to find housing suitable for them and help them reintegrate in the community.

Beth Huebner (University of Missouri) and her associates also found that there was little evidence residence restrictions had a significant impact on the rate of recidivism among sex offenders after release. Missouri saw a decrease in recidivism after the introduction of residence restrictions, while Michigan witnessed a slight increase. Huebner, Huebner and others reported their findings here Criminology & Public PolicyAccording to, “The results warn against widespread and homogenous application of residence restrictions.”

Florida University reported on a study in Criminal Justice and BehaviorComparisons of recidivists and nonrecidivists showed that “no significant association” between reoffending, proximity to schools and daycares. According to the authors, “proximity of schools or daycares with similar risk factors does not seem to be a contributing factor to sexual recidivism.”

A 2019 Yale Law Journal Allison Frankel (a Human Rights Watch Fellow) examined New York’s situation. Ortiz noted that finding housing is difficult for sex-offender registrants. She said that there are restrictions on who can be convicted and how they may be able to live in New York City. She observed that the state’s current detention policy continues despite evidence that sex-offenders’ recidivism rates remain low and that residence restrictions don’t prevent sexual offenses. “Rather such laws condemn registrants homelessness and joblessness as well as social isolation.”

Is it possible that residence restrictions are irrational and fail to pass the rational basis test because they lack logic? Federal appeals court agreed. U.S. Court of Appeals 6th Circuit ruled 2016 that Michigan’s registration requirements, which included residence restrictions, were retroactively applied to sex offenders. This was in violation of the constitutional prohibition on ex post facto laws. A three-judge panel found that Michigan’s policy was not connected to a nonpunitive goal.

6th Circuit stated that the research did not back Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s claim that recidivism rates among sex offenders were “frighteningly and high.” According to the court, there is “evidence” in support of the finding that offense-based registration does not have an impact on recidivism. It stated, “nothing that has been pointed to by the parties in the record indicates that residential restrictions have any benefit on recidivism rate.”

The California Supreme Court in 2015 was not impressed by the justification of a rule 2,000 feet that covered everyone on the state’s list of sex-offenders. The policy was “not rationally related to the legitimate state goal of protecting children against sexual predators,” it said.

Judge Rowan Wilson argued, in his dissent against the New York Court of Appeals’ decision against Ortiz: The prisoner’s claims deserve heightened scrutiny. However, even though he believed the majority had been right in applying the rational foundation test to Ortiz’s claims, Judge Rowan Wilson stated that it was not clear whether New York’s detention policy could satisfy this minimal standard.

Wilson admitted that “the rational basis test” is not a strict one. Wilson acknowledged that rational basis review was a gentle and thoughtful process, but it’s not intended to be toothless. Wilson explained that Wilson’s standard required “that the State act be reasonable, logical, and sensible” even though it is minimally. In other words, the State must not take any action that is unjustified, counterfactual or groundless.

Although “the stated government interest in preventing sexual victimization

Wilson said that while children’s rights are “clearly legitimate”, Wilson stated, Wilson’s choice of means to protect children from sex crimes is not rational. According to Wilson, “courts as well as scholars” have accepted that residence restrictions are almost ineffective at preventing children being victims of sexual crimes. He said that continued imprisonment on the basis of this policy “irrationally hinders the New York State’s and City Legislatures’ goals to foster the success of reintegration for formerly imprisoned individuals into the community.”

The supreme courts of several states, including Alaska, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania, have reached conclusions regarding sex offender registries similar to the 6th Circuit’s, deeming these schemes punitive rather than regulatory. It’s clear that when registration requirements are used to prolong imprisonment (as they did for Ortiz), it is imposed punishment under another name.