People who make a felony. intentional murder—and only those people—should be executed. This is a position I have held almost all my adult lives.

It has been a long debate on the death penalty. It has been my profession over the years reading the various contradicting research on the effectiveness of the penalty. It didn’t matter if executions of murderers have a deterrent effect. Capital punishment is what I support because I believe in justice.

My nature is peaceful and I haven’t gotten into any fights since I was a teenager. However, my idea of what is right is determined by my thoughts about what I would do for someone who has willfully killed me, my family members, or a close friend. Inflict barbarous Atonement for an unjust act. The main purpose of state-announced execution is to keep social peace and avoid blood feuds.

It was not just me who advocated death sentences for criminals. Gallup indicates that in the first decade, an average of 66 per cent of Americans supported death sentences for those convicted of murder. However, this number has fallen to 55% by 2020. Gallup documented a growing gap between Republicans and Democrats on this issue over the last two decades. A solid 80 percent of Republicans support the death penalty, while Democratic support is down to below 40 percent.

However, any partisan strife over the death penalty was relatively insignificant compared with the increasing discord on issues like guns, affirmative-action, climate change, vaccinations, and other controversial topics. According to research, Americans are more likely to align their views on hot-button topics along party lines.

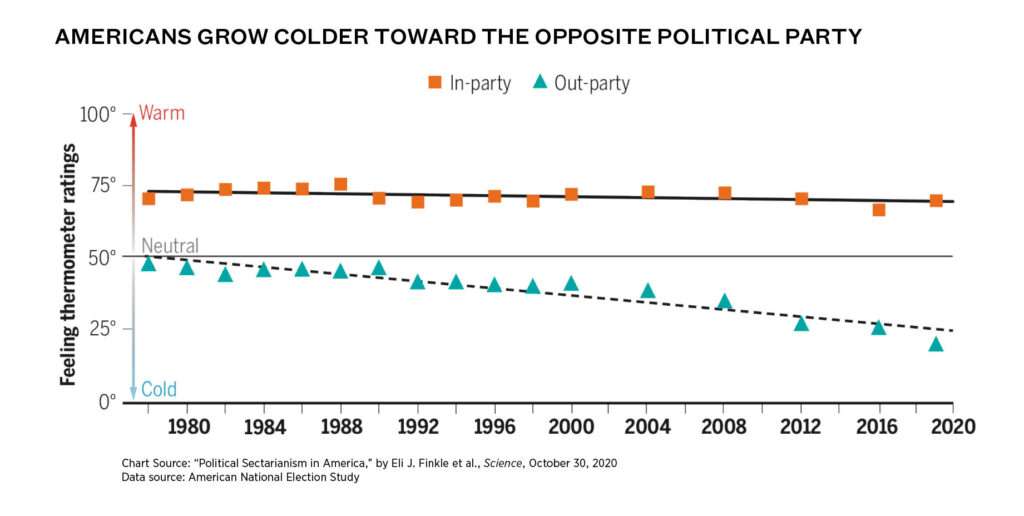

Statistically, members who are not affiliated with one of the major American parties are more inclined to distrust or dislike the member from the other. Your dislike for the other party is growing, even though your love for it hasn’t grown over recent years. It is difficult to trust news outlets from the opposing side. You feel increasingly alienated by its supporters: not only in terms of partisan affiliation, but also in terms of social, cultural and economic characteristics. In some ways, you may consider them subhuman.

It is also possible to be Wrong about the characteristics of members of the other party, about what they actually believe, and even about their views of you. Confirmation bias can make you feel like you’re in prison. Confronting facts that are contrary to your beliefs does not alter them. In fact, it can even strengthen them. In a perverse way, partisans who are vilified by the opposing party will behave exactly in the same norm-violating or game-rigging manner as their rivals. This is a vicious circle that’s getting worse and more dangerous.

They also keep people stuck in preexisting worldviews. I am a libertarian and don’t find the traditional left/right split on many issues of public policy relevant. My unease over the death penalty grew, but I felt an immense reluctance in my own self to change my mind and give up on previous commitments. Is it difficult to admit that you’re wrong?

A term is used by social scientists to describe the phenomena described above. affective polarization. That refers to Democrats and Republicans growing dislike for and distrust of each other in the U.S.

Eli Finkel, a Northwestern University psychologist and his co-workers have attempted to measure this phenomenon since 1978 using a thermometer. According to the thermometer, Americans describe how they feel about co-partisans on a scale from 0 degrees to 100 degrees. They report between 70 and 75 degrees. Opposition partisan feelings have plunged from 48°C in 1970s to 20°C today. This is an emotional cold snap. “Since 2012—and for the first time on record—out-party hate has been stronger than in-party love,” they write in the October 30, 2020, issue of Science.

Other studies show the consequences of this chill, including those of Nathan Kalmoe from Louisiana State University and Lilliana Mason at the University of Maryland. One of their more striking results is that 60 percent to 70 percent of both parties in a 2017–18 survey said they thought the other party was a “serious threat to the United States and its people”; 40 percent of respondents in both parties thought the other party was “downright evil.” A second poll showed that 15% of Republicans and 20% of Democrats agree with the sentiment that the country will be more successful if the number of opposed partisans living today is small. A further 18% of Democrats, and 13% of Republicans agreed that violence could be justified if the opposition party wins the 2020 presidential election.

The results of such studies indicate that there’s something significantly more to the rise in partisanship over recent years. And that this trend won’t go away.

Americans seem to be more critical of their political adversaries. People may take their cues form political elites to some degree. A comparison of the votes recorded by Republican and Democratic lawmakers reveals a sharply rising partisan divide in Congress over the past 70 years. The 2018 Congress Electoral Studies article on how party elite polarization affects voters, the Texas Tech political scientist Kevin K. Banda and the University of Massachusetts Lowell political scientist John Cluverius find that “partisans respond to increasing levels of elite polarization by expressing higher levels of affective polarization, i.e. More negative opinions of opposing parties than their own.

Steven Webster, Emory University’s political scientist, and Alan Abramowitz, have tracked the increasing mutual hatred of Republican and Democratic partisans and noted that growing ideological distance among Republican Party elites could be contributing to greater partisanpolarization.

Additionally, the correlation between partisan affiliation and other political or social divisions was much lower in past decades. Nicholas Davis, the Louisiana State University’s political scientist, has analyzed data collected by YouGov/Polimetrix from 1948 through 2012. The two researchers report in a working paper that the stronger and more aligned their religious, racial and partisan identities, the closer our political parties are to our ideologies. Increased ideological consistency correlates with increased partisan biases and intolerance among the electorate.

Partisans are still wildly exaggerating the differences in substance between the parties, even with an increasing ideological divide.

A 2015 YouGov poll found that 32% of Democrats were LGBT and 29% are atheists and agnostics. 39 percent also belong to unions. The correct figures, however, are 6, 9 and 11%, respectively. The survey also found that 38 percent of Republicans earned more than $250,000 annually, 39% are older and 42% are evangelicals. In reality, only 2 percent make that amount, while 21 percent and 34% are both senior citizens.

Democrats and Republicans both often overestimate how deeply their adversaries hate them. A sliding scale of 0 (lowest evolved) to 100 (10 most evolved), Republicans gave humanity scores of around 85 points while Democrats scored 62. That’s a 23-point gap. The opposite was true for Democrats, who gave only 62 points of their political friends, and 83 to Republicans. This is a 21-point gap. It is even more remarkable that Democrats thought that Republicans would only award them 36 points, which was 26 points lower than the actual number. Republicans however estimated that Democrats would grant them only 28 points (34 less than what the truth number).

Samantha Moore Berg, University of Pennsylvania Political Scientist and her co-authors concluded that Democrats and Republicans are equally hostile to and dehumanize others in 2020 research published by the Proceedings of National Academy of SciencesBut, think about the fact that prejudices and dehumanization are twice as high as those reported by Republicans and Democrats.

One of the more dire consequences of this exaggerated meta-perception—the perception partisans have of the other side’s perception of them—is that it seems to make people more willing to support illiberal and antidemocratic policies, such as curbs on free speech and political participation.

Moore-Berg and others found similar results in the 2021 study of Alexander Landry, University of California Santa Barbara socio scientist, and his associates. They further discovered that, “despite liberal liberalism’s socially progressive outlook, most liberal Democrats dehumanize Republicans the most.” Democrats showed greater outgroup hatred than Republicans.

Milan Svolik, a Yale political scientist, and Matthew Graham were asked by partisans whether they would continue to support the party’s standard-bearers if these policies violated democratic norms. One of the proposed policies was a redistricting program that would allow their own party to gain two more seats in spite of a drop at the polls. Another proposal is to cut the number polling stations located near strong opposition parties. Only a few voters were willing to withdraw their support of politicians in their party’s opposition parties if they violate such norms, according to the researchers. They conclude that, “Put simply,” their estimates indicate that in large numbers of U.S. House Districts, the majority-party candidate can openly and without any consequences, violating one of our democratic principles.

Kalmoe & Mason found that around 20% of Republicans and Democrats agreed with Mason that their parties should not break any rules in opposition to the other party because it is necessary for the good of the country.

These views are often incorrect. Could more information about the other party help to solve this problem? Research has consistently shown that political parties tend to believe what they see, regardless of the costs.

A 2012 experiment showed the same protest video to partisan viewers. Participants believed that the video showed liberal-minded protesters. Republicans were more supportive of police intervention than Democrats when the video was shown as a protest by conservatives. Jay J. from New York University observed, “Opposing an Abortion Clinic,” Jay J. Van Bavel, Andrea Pereira (Leiden University), in an 2018 Cognitive Science: Trends article. Faced with similar visual information, different people may have drawn different conclusions based on political affiliation.

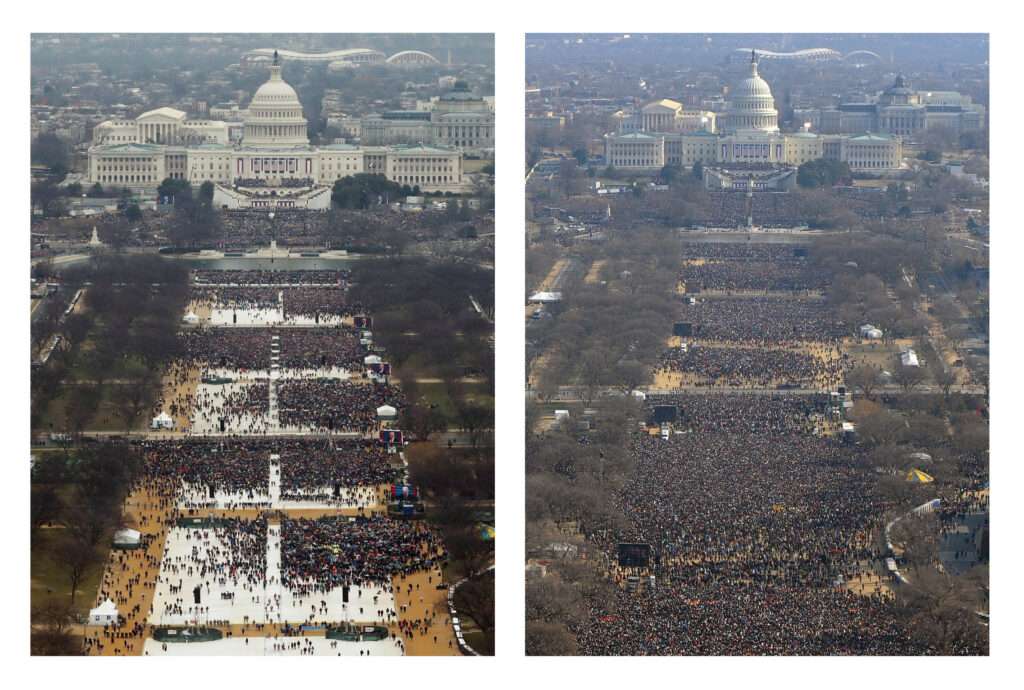

Are partisans seeing things differently? Maybe they cheer for their team more than standing up for actual beliefs. Michael Hannon, University of Nottingham philosopher, has explored this idea in a 2020 paper. Political epistemology. A survey of almost 1,400 Americans was conducted by him in January 2017. The researchers showed photos of half the respondents, with only one label. and B, of the crowds on the National Mall during Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration Donald Trump’s 2017 inauguration. They were asked which photo depicted the crowd for each president. Forty-one percent of Trump voters said the photo with the larger crowd depicted the Trump inauguration, which was actually the one from the Obama inauguration. Only 8 percent of Hillary Clinton voters picked the wrong photo. The researchers argue that it is likely that Trump voters picked the photo with the larger crowd as a way to express their partisan loyalties and show their support for him.

More tellingly, the researchers asked the other half of the respondents which photo depicted the larger crowd. One answer was clearly correct. But Trump voters were seven times more likely To assert that Trump’s inaugural photo had more people, (15%) is better than Clinton voters (2%) Amazingly, 26% of Trump voters have incorrectly answered with college degrees. When a Republican claims Trump’s inauguration photo contains more people than they actually believe, it is not arguing with others. Hannon says they’re cheerleading. People are only making assertions about facts to show their loyalty to one particular ideology community.

Partisan cheerleading sounds harmless—not much different from fans rooting for a local football team, right? Nope. Hannon claims that “if we disagree on the basis of genuine reasons and arguments, then it is impossible to engage with each others’ views.” Hannon says that team loyalty is what is important. “We cannot reduce polarization through reasoned discussion.”

The 2015 Study in Quarterly Journal of Political Science sought to distinguish partisan cheerleading from sincere partisan divergence. John Bullock, a Northwestern University political scientist and his associates found that small amounts of money were offered to participants for correct or “don’t understand” answers to politically relevant questions. This reduced the gap between Republicans and Democrats around 80 percent.

To the extent that facts are influenced by politics, paying partisans not to correct factual questions should not be considered a payment. It does, however,” they point out. They observe that small payments can significantly decrease the gap between Democrats of Republicans. These results suggest that Democrats and Republicans don’t hold fundamentally different opinions about many key facts. These results have prompted the researchers to urge analysts of public opinions to consider the possibility that “the appearance of polarization” in American politics may be an illusion of survey measurement, rather than evidence for real differences in the assessment of facts.

On the other hand is a series of experiments conducted by the Texas A&M political scientist Erik Peterson and the Stanford political scientist Shanto Iyengar. They report on their findings in an article for 2021. American Journal of Political Science they asked Republican and Democratic partisans to evaluate the truth of claims about several hot-button issues, such as “illegal immigrants commit violent crime at a significantly higher rate than legal American citizens” and “40 percent of firearm sales in the U.S. occur without a background check.” In both instances, the right answer was They do not.) Researchers found that 97% of Democrats had the correct answer to immigrant crimes compared with 45 percent for Republicans. On gun sales however, only 22% of Democrats had the correct answer, while 56% of Republicans did.

Peterson, Iyengar provided access to news sources for respondents so that they could confirm their beliefs. They provided access to sources that could be associated with conservative and liberal partisan loyalties. These sources included so-called mainstream news sources as well as expert sources from peer reviewed journals. Only 7 percent referred to sources from outside parties, while 26% turned to experts sources.

Another set of participants was offered a small financial incentive in return for giving accurate responses. They also had access to various news sources. They found that “roughly 60% to 70%” of initial differences in partisanship remained even after the incentive. While this is encouraging evidence, it suggests that most partisans believe inaccurate and resolute claims.

Peterson and Iyengar suggested that if unincentivized political partisans do a lot of cheerleading, their reliance on comforting partisan news sources should decrease when they receive a correct response. However, financial incentives would have no effect on partisans’ preference for biased news if they were confident their answers are correct. Peterson and Iyengar reported that financial incentives do not have any effect on news selection.

Peterson and Iyengar also had almost 900 people participate in their experiments. In the wild, participants relied on news sources that supported their views.

Political sectarians have plenty of information to choose from. They can find news that supports their ideology and discredits those of their opposition on the internet, which is why there are so many partisan media outlets like Fox News and MSNBC. The 2019 election will see a significant increase in the number of people who are able to vote. Psychological Science: Perspectives review of 51 studies testing for political bias found that “both liberals and conservatives were biased in favor of information that confirmed their political beliefs, and the two groups were biased to very similar degrees.”

Peterson and Iyengar concluded that “our studies show that partisans are truly committed to inaccurate beliefs they report on surveys.” Confirmation bias is all around.

This may be the only way out. Perhaps it’s time to think about why some partisans are so certain their opinions are correct.

Hrishikesh, a Bowling Green State University philosopher, made this point in his 2020 paper, “What Are The Chances You’re Correct About Everything?” The list includes nine politically charged propositions. Abortion is wrong. A carbon tax is good idea. Illegal immigration is a problem. Gun ownership controls should increase. Racial affirmative in college admissions should not be justified. African Americans are being unfairly targeted. There are too many regulations for U.S. businesses.

Joshi contends that these propositions are orthogonal—that is, your position on one doesn’t necessarily commit you to any particular position with respect to the others. You should not rely on your position on abortion rights to determine what you think about climate change. We all know from experience that asking people their opinions on hot-button issues can help us determine where they stand with Joshi’s other nine. They are more likely to support affirmative action if they believe in gun control. They are more likely to believe that business is too regulated if they do not support gun control.

Joshi wrote that “Since both sides differ with respect to many political issues,” Joshi said, “One side getting it right implies the other side getting things wrong consistently.” Each side’s political adversaries “consistently get the wrong answer in relation to large areas of rationally separate political questions!” Joshi believes that such opponents are not reliable. anti-reliableThey will always choose the wrong solution for every issue. He challenged partisans “to identify psychological differences between liberals and conservatives that could plausibly explain why one side cannot be trusted with regard to issues of partisan dispute.”

Joshi is open to exploring different possibilities. There is a possibility that they could be wrong because they hold a fundamental false belief.

Joshi, for example, advocates a libertarian view in a night-watchman-state with limited government. Proponents of a large social welfare state believe that such a libertarian is unreliable in funding universal healthcare, generous unemployment insurance and subsidised housing for those with low incomes. But as Joshi points out, these issues are related to the libertarian’s core belief and so are not orthogonal—that is, they are rationally related to one another.

Joshi examines possible explanations to the lack of trustworthiness among partisan opponents. Are partisans generally smarter than their counterparts? But not really. Joshi refers to a 2019 study “(IdeoLogical Reasoning): Ideology Impairs sound Reasoning” that showed that both liberals and conservatives had a tendency to disregard the validity of classically-structured logical syllogisms, in order to draw conclusions that were supportive of their political beliefs. (He mentions that a 2018 study by Danish psychologists found that higher cognitive ability is associated with more social liberty and greater economic conservatism. That combination might sound familiar to libertarians.

Joshi says that neither conservatives nor liberals have shown greater distrust in scientific knowledge. However, greater science literacy correlates to more strongly held beliefs, such as those on climate change or stem cell research. Also, being more knowledgeable may make it easier to defend nonscientific positions.

A second possibility is that your political opponents may be consistently wrong because of their obsession with perverse morals. A 2018 study found that the majority of respondents were not aware. Psychology in PoliticsAccording to the study “Deep alignment with Country or Political Party Shrinks The Gap between Conservatives’ and Liberals’ Moral Values”, conservatives and liberals have broadly the same moral foundations.

In the end, however, liberals as well as conservatives are not fundamentally different in how they formulate their opinions. Joshi says that Joshi’s argument suggests that partisans are unable to account for why their opponents might be unreliable.

Michael Huemer, a University of Colorado philosopher, says that it is impossible to imagine people who gravitate toward falsity. Even if some people aren’t very adept at finding the truth (they might be stupid or irrational), it is still possible to get there.At worst, their beliefs should not be. Unrelated They should be directed in a systematic manner, contrary to popular belief Go away From the truth. While there may be one true cluster of political beliefs, this analysis strongly suggests that it is not the case.

Joshi recognizes that anti-reliability arguments against opponents don’t apply to Marxists, libertarians and other people whose opinions on politics are grounded in a core principle. Five of the nine statements Joshi mentions are mine. He instead applies his analysis to partisans who are able to hold almost all of the views on the right/left side. Joshi says that it is more than disagreement with someone who causes problems for a partisan. It is because political beliefs are dispersed across the country in such an oblique way that it makes it extremely unlikely that a partisan believes all of them are correct. This suggests that partisans must be more confident about their beliefs.

Joshi recommends that partisans engage in dialogue with those who have the most persuasive arguments to support their opponent’s convictions. He is a mirror of John Stuart Mill’s advice. Liberty“He who only knows his side of the story, doesn’t know much about it.” Although his reasons might be valid, no one could refute them. He cannot refute those on the other side, but he doesn’t even know the facts. This is why he can’t choose one.

A fascinating 2020 study by the Journal of Experimental Social PsychologyA Duke team of psychologists found that Americans are more likely to distrust and denigrate their ideologic opponents when it comes to current social and political issues. Why? Maybe partisans believe that opponents don’t have strong reasons to support their opinions, which leads them to assume their opponents are intellectually and morally weak. Researchers at Duke wondered what might happen if we gave partisans arguments from their opposition on issues like concealed gun carrying, mandatory body-worn surveillance on police and universal healthcare.

Good news: partisans reported less often that they believed their opponent lacked moral or intellectual character, when given reasons in support of their view. The researchers conclude that the results show reasons have a new function, which is distinct from decision making, persuasion and acquiring knowledge. Our results suggest that even though the presentation of different reasons may not cause a person to change their position, it might make them less likely view others negatively. This might lead to people being more open to listening to their adversaries and willing to have genuine discussions with them. It could have positive consequences for compromise, productive deliberation and pursuit of the common good.

Let’s now look at the political split on the death penalty. In arguments with colleagues, friends and random strangers I encountered in bars as well as my wife, I supported capital punishment for years. While I doubt I persuaded anybody to change their mind, I do hope so, as I gave it. There are many reasons for my position, at least some of my interlocutors concluded that I was not entirely lacking in intellect and morals.

Many of my adversaries’ desire to abolish capital punishment stemmed from their hatred of state-sanctioned execution. These modern-day civilized individuals, they claimed, cannot accept such cruelty. They knew that this was not my view. Then they would point to studies that claimed the death penalty didn’t deter murderers. I, of course, sought to persuade them using the same sort of evidence—that is, contrary research showing that the death penalty did deter would-be murderers.

These back-and forth arguments for years did not stop me from wanting to inflict vengeful justice upon those who had previously killed others with such brutal malice.

My opponents made one objection to the death penalty, and it pierced my heart: The possibility that someone innocent might be wrongfully executed because he/she did not murder. As evidence, they would point to the rising number—the count currently stands at 186—of people exonerated after being confined to death row. It was troubling. I will respond that none of the 1,500 executed people were found guilty after 1976’s Supreme Court reinstated death penalty.

In 2021, DNA testing on the genetic material of Ledell Lee’s murder weapon revealed that it was a later date. This led to the discovery of an unidentified person. The state of Arkansas executed Lee for his murder four years ago. Although he may have been guilty of the crime, I believe the evidence to the contrary that Lee was executed by the Arkansas government for his innocence is quite convincing.

The desire to seek retribution is not diminished in any way. The arguments that I heard from my colleagues, friends, bar patrons and even my wife over the years convinced me that the death sentence cannot be justified. But I was mistaken to have supported it.

Changing my mind on this topic was wrenchingly difficult—and this despite the fact that I was joining my fellow libertarians, who for the most part oppose the death penalty administered by the state, meaning that I had little at stake in terms of my other prior commitments.

The increasing affective polarization among partisans is evident from everyday experiences and political science data. Americans are more likely to believe what they have already believed and reject contradictory information. This perpetuates and expands the political divide.

Joshi persuasively refutes the belief that only one wing of the right-left spectrum can be right on all issues. Joshi argues that it is not so. He encourages partisans be less certain of their views, and instead seek out and engage their best opponents’ arguments. Other recent research shows that even partisans who are presented with arguments in favor of their opponent’s views think better about them. It begs the question: Is it possible that today’s partisans won’t shout past each other long enough to see that their opponents may actually have something to say?

The fact that it took decades for my friends and colleagues to persuade me that I was wrong about the death penalty—even in the absence of strong affective polarization—is not a good omen.