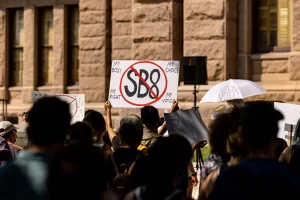

Stephen Sachs (co-blogger) responds to my recent post. Sachs argued that Texas’ SB 8 antiabortion law is more vulnerable than a Supreme Court decision in its favor. Partly, I wrote my response to Steve’s earlier post.

Steve recently contributed to the discussion and explained that his concern was not for slippery slopes, rather, it is about “principles”.

A demand is made for the application of certain limiting principles. For principles—a demand that the Court be principled in reaching its decision, that its judgment follow from premises that it’s willing to defend in other cases too.

I think such principles are very important. My concern over the dangers of SB 8’s slippery slope is shared by others. But, ultimately it is a concern about the risk to an essential principle. It is important to remember that the Constitution’s judicial protection cannot be weakened by state governments. As explained by me in an earlier post and highlighted by many justices during oral argument, Texas could be accused of using similar tools to subvert a range other constitutional rights such as gun rights and property rights.

Preventing this outcome is an essential principle and, in Steve’s words, a “premise.” [the Court should be]Willing to assist in defense of other cases. Courts should stop allowing a state to pass a law that prevents federal judicial review of legislation that may violate constitutional rights. This should not be allowed if it means that precedents regarding sovereign immunity or limitations on plaintiffs’ rights to sue for enjoinment judges must be overruled. In cases of conflict, these principles should be abandoned.

In my earlier post, I discussed some reasons why judicial reviews should be preferred to other factors. While I would be happy to get rid of sovereign immunity almost entirely (and the same for artificial distinctions between enjoining judges and enjoining other state officials), ruling against Texas in this case would not require going that far. Only the Supreme Court will have to rule that sovereign immunity must yield in cases that create serious “chilling effects” on a constitutionally protected right. These “chilling” effects are already grounds for preenforcement suits in many other situations, including freedom of speech. This argument for prioritization holds especially true when it comes to rights that are protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish a case involving chilling effects from one that doesn’t pose such danger. This is not more than the case of interpreting many other Constitutional Law doctrines, where courts have to enforce a standard rule rather than a bright-line one.

The Supreme Court does not have to grant every state judge a wide right to injunctive relief (a topic Steve raised in another post). Again, it might be limited to cases of chilling effect. The injunction could also be used to stop judges from suing clerks and other officials who are essential for a SB 8 lawsuit or similar cause of action formulated by another state following the SB 8 model. If you cannot or will not allow people sue to enjoin the judge, let them sue to enjoin the clerk, the janitor, the bailiff, or whatever other less-exalted official needs to be stopped to forestall SB 8 lawsuits.

These distinctions between state judges, and the lesser officers who assist them in doing their jobs are artificial and silly. The Supreme Court should just cut through the Gordian knot, and declare that state judges are able to be injected the same as any other state official who violates constitutional rights. However, the Supreme Court may not be willing to make this decision. In my opinion, the targeting of lesser officials is far more problematic than the SB 8 subterfuge, which would put at risk many constitutional rights.

Steve and others conclude that the best remedy for constitutional rights is going to Congress, regardless of whether the SB 8 Strategy poses a significant threat. This argument disregards the fundamental principle that judicial reviews are intended to preserve constitutional rights in cases where elected officials cannot or won’t do so. The only way to avoid judicial review is if the legislature could do this job.

Although the points above are not likely to convince those who think that sovereign immunity protection and rules against state judges being enjoined by the judiciary are more important than constitutional rights protection, they are still worth considering. However, I bet that those with this rank of preference are very few – even on the Supreme Court.

We should choose the one that is more important when two principles clash. You can call it a meta principle. It is also an idea judges should consider applying to future cases.